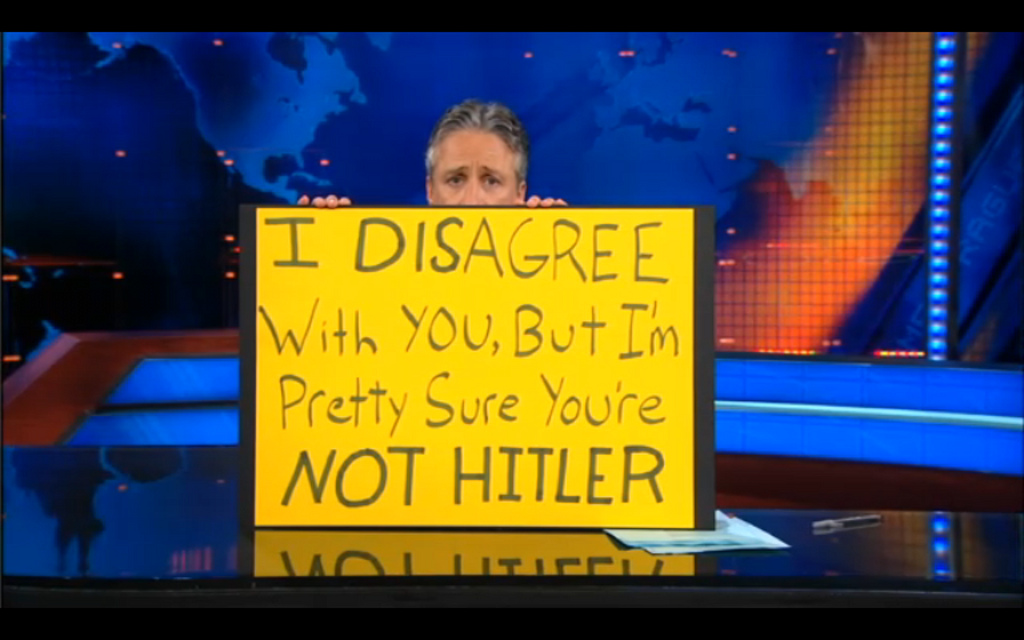

Being Disagree-able

Disagreements suck.

It is never fun to be at odds with someone, especially if that someone is a person you’re working with or who is in charge of paying you money.

But disagreements happen. They are a part of life and they are definitely a part of work. Instead of hoping really, really hard that the impossible occurs and the remainder of your days are filled with joyful collaboration, prepare for disagreements by learning to be better at them.

Step One: Listen.

Listening is a skill that just about everyone knows is vitally important and that most people don’t do very well at all.

It’s hard, first off, because it means that whenever the other person is talking, you have to make them the most important person in the conversation. If you don’t, if you treat them as if they are, say, most important after you, it will be very difficult for you to hear what they’re really saying.

Does this mean you fawn over them and their every word? No. Does this mean you agree with everything they say? No. Does it mean you make their arguments more important than your own? No.

It means that while they are talking you do not spend your time thinking up the Best Retort Ever™. You pay attention to what they are saying.

It means that you notice patterns they’re using, phrases that are repeated or body language that they use when particular subjects come up. You do your best to determine if the patterns have negative or positive connotations. You remember these patterns.

It means you pay attention to the context in which things are said. And you don’t ignore that context when you interpret what the other person is saying.

Listening is the most important part to disagreeing because listening is what will tell you what is important to the other person. And if you don’t know what is important to the other person, you don’t really know why, or even if, you are disagreeing.

You also need to know what is important to the other person because if you want them to agree with you, you need to present your arguments in a way that is meaningful for them. If your arguments aren’t meaningful to them, they will not be persuasive.

Listen to what the other person is telling you and two-thirds of the work of being a good disagree-er is taken care of.

Step Two: Put Your Arguments in Their Context.

You know what you want because you know how it will impact you. That is fantastic. The other person does not care.

They care about themselves and what they want and how what you want will impact them.

Most people disagree poorly because they keep repeating their arguments in context of how it will impact themselves.

Eg., “You should give me a cookie because it will make me happy.”

If the person with whom they are disagreeing doesn’t seem to grasp the importance of getting a cookie, they often try to make their point by emphatically repeating how important this really is. “Everyone else has a cookie and I feel left out; if I have a cookie I will feel better.”

When this doesn’t work, they resort to accusing the other person of not wanting them to be happy. “If you really loved me you would….”

Guilt does not a productive relationship make, friends.

So don’t talk about you when presenting your arguments, talk about the other person.

Because you listened, you know what’s important to them. Use this knowledge when explaining why you want what you want.

“Illana, I know you’re concerned that this book won’t sell because teachers and parents will think it’s ‘too old’ for middle school kids. I also know this is the right narrative choice because it will resonate better with those kids. Here are a few stories where I’ve seen similar narrative choices made and their popularity indicates to me that this choice won’t negatively impact our sales numbers.”

If your counterpart is worried about sales numbers, don’t present your argument purely in terms of narrative structure. If they focus on printing costs, don’t sell them your ideas entirely based on being cutting edge.

Good decisions work for a number of reasons. When arguing why your decision is the best one, use the reasoning that will mean the most to the person you’re talking with, not the reasoning that makes the best sense to you.

Step Three: When Talking About Your Interests, Speak Clearly.

I don’t mean take the marbles out of your mouth before you begin talking (though, that’s a good idea, too). I mean that when you disagree with someone, it’s important that you speak frankly and directly, with the level of respect you’d like them to show you.

This isn’t usually a problem in disagreements with a stranger in a bar or about this past season of Dr. Who. In these situations, where the disagreement isn’t likely to have a lasting impact, we tend to be much braver in asserting our opinions. It’s no surprise; these disagreements pose little risk.

When we disagree with people with whom we have ongoing relationships, however, the risk increases and we tend to cloak our wants and needs in language that feels “nicer.” The direct language we’d use in a low risk situation can suddenly feel garish and blunt. We’ll incessantly hint at what we want to say to avoid having to actually say it to their face.

When I say “speak clearly” I mean you need to say it to their face.

And if you have the opportunity to do so, I literally mean “to their face.” Disagreements, like all other emotional conversations, are best had face-to-face. But if that’s not possible, if the person you’re disagreeing with is on the other side of the country or the world, you still need to be direct with them. You need to be clear about what you want, why you want it and why the offered solution doesn’t work for you.

This advice isn’t easy to follow. Partially because it requires you to be somewhat confrontational, but also because it requires you to be very aware of what you’re actually saying to the other person. We often think we’re being abundantly clear even when we’re pitching a softer version of our opinions.

Be respectful, but be direct. When they respond, if they don’t seem to have understood what you’re saying, calmly say it again. Make sure you’re using language that is meaningful to them (see step two, above) and if one approach doesn’t work, it’s OK to change how you present the information, so long as you don’t change the information itself.

The important thing is that you don’t shy away from the conversation when the other person doesn’t appear to understand you. Not being understood is frustrating and it can make you want to give up. Don’t. Use steps one and two above to help you stay in the conversation and make sure you are heard.

Disagreements are going to happen, but you can learn how to disagree in a way that is productive and helpful. Listen, put your arguments in a context that is meaningful to the other person and be direct. You’ll be amazed by how much easier your disagreements are.

Featured Image by Ninj0x via Flickr.com.

Categories: Dealing with People