Ghost Rider and the No Good, Very Bad Contract

I get a lot of questions about what a “good” contract looks like. It’s a tough question because “good” depends on what you need the contract to do. A contract that works really well in one instance might be a flaming pile of trash in another.

What I can do is show you what unhelpful contracts look like — contracts that everyone thought were going to be just fine but turn out to be unclear and hard to figure out.

This week, our unhelpful contract example is courtesy of none other than Marvel.

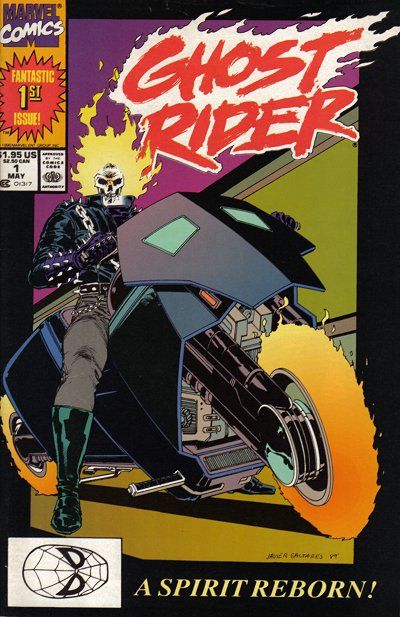

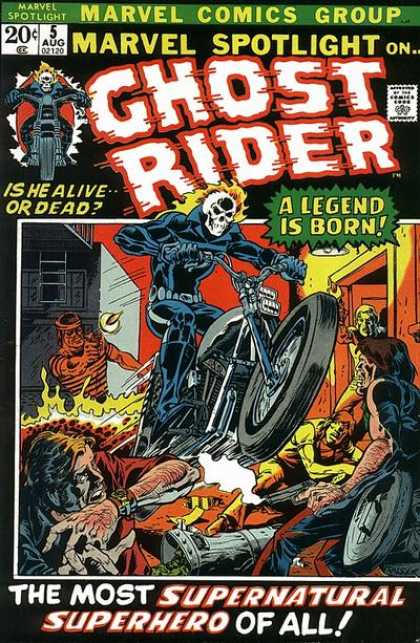

Earlier this month an appellate court came out with an opinion regarding a contract Marvel used in the late 1970s. This particular contract was signed by Gary Friedrich, the creator of the character Ghost Rider.

The one-page contract said that Ghost Rider was a work made for hire and that Friedrich “expressly grant[ed] to MARVEL forever all rights of any kind and nature in and to the Work.”

When he signed the agreement Friedrich was told it only covered future work (even though the contract said differently) and that if he wanted any future work with Marvel he had to sign it. (Sound familiar?)

Marvel never hired him to do work again.

When Ghost Rider became a video game/movie/brief money maker in the early aughts, the disagreement about the contract arose. Had Friedrich really signed away all of his interest in the character? Did Marvel hold the copyright in the originally published story? Why was Nicholas Cage cast as Ghost Rider?

I like this example of a not-so-great contract because it has a lot of familiar elements — it’s short, it’s about the creator getting a story he loved published and it involves the seemingly simple but often messy world of work made for hire agreements.

Let’s dig in, shall we?

Length

I often hear artists worry about a contract being “too long” and wishing that instead they could just sign off on a simple, one-page document.

Please, I beg of you: Don’t confuse the length of the contract with the clarity of the contract.

Most people who worry about the contract being too long are really worried about the contract being too confusing. Wanting the contract to be clear and easy to read is a good thing! But thinking that clarity is somehow tied to brevity isn’t.

With short contracts I always worry about what’s missing. What isn’t being said in that short contract that you might need later on?

With long contracts I worry about what’s been tucked away in the crevasses. What might rear its ugly head in a year or 30?

It is a lot easier to find what’s rotten than to try and figure out what isn’t there.

So, remember: there are incredibly crappy contracts that are a page long and hugely valuable contracts that span dozens of pages. It doesn’t matter how long or short a contract is, it matters how clear the contract is.

What They Tell You Doesn’t Matter

Remember that “trust me, it’s only for future work” assurance that Friedrich got?

What do you think Marvel argued in court?

If you guessed that they argued they owned everything ever having to do with Ghost Rider, including the stuff that was created years and years before Friedrich signed the contract: good job, give yourself a cookie!

Contracts are often interpreted by people that weren’t around when they were signed. People who don’t know the backstory or care about who said what to whom before pen hit paper.

Contracts are interpreted by strangers. So make sure a stranger can pick up your contract, read it through and understand what you really agreed to.

If the contract language contradicts what you think the deal is: don’t sign it.

If not signing it isn’t an option, change the language.

If the contract is a preprinted form that you can’t go back and retype, take your pen and cross out what’s wrong.

If they hand a new, unblemished contract back to you and say, “sorry, no changes,” then decide if the deal is worth agreeing to what’s on paper because that’s the deal that will matter.

“Work Made For Hire” and Ideas

I’ve talked about work made for hire agreements before, and if you’re a freelancer of any stripe you’ve probably seen your fair share of them.

(If you aren’t familiar, or want to learn more about them, this is a fantastic overview.)

People buying your stuff like work for hire agreements because it means that from the moment of the creation of the thing you’re making for them they are the owner of the copyright.

But they do actually have to follow a few rules for something to be a real work for hire and, don’t be shocked, many people don’t follow the rules.

The rule that played a big part in the Ghost Rider opinion is whether the work was “specially commissioned.” For a work to qualify as a “work made for hire” the hiring party needs to commission the work; they have the idea and they are hiring you for the specific purpose of bringing that idea to life in a particular way.

Well Marvel didn’t think up Ghost Rider. Friedrich had been working on the character for years, since at least the 1950s. He brought the idea to Marvel and, after much hemming and hawing, Marvel agreed to publish a Ghost Rider story in Marvel Spotlight #5 to test the idea out.

Sounds like a slam dunk, right? Marvel didn’t commission Ghost Rider; Friedrich’s got this one in the bag!

But in all those years of thinking and loving that character and story, Friedrich never wrote down anything about Ghost Rider.

Nothing. Nada. Not a line; not a word.

So guess what? Up until Friedrich wrote out a pitch synopsis at Marvel’s suggestion, Ghost Rider and everything about him was just an idea.

Ideas aren’t protected by copyright.

Copyright only protects the expression of ideas. Why? Because it would be really crappy if someone got to corner the market on “sunsets” just because they thought about it first.

So if you love an idea you have and you can’t stop thinking about it: MAKE IT.

Don’t wait for someone to tell you it’s OK or that they like it or that they want to help you turn your idea into reality. Don’t spend time thinking about how you want to make it perfect, just make it.

So who owns Ghost Rider? Because the contract was so murky and because there are so many conflicting facts about who did what when and why, the question of who owns the copyright to the original Ghost Rider story is still up in the air. The appellate court sent the case back down to the trial court and said, “figure it out.”

That means more money and more time and more energy will be poured into resolving what this simple, one-page contract really means.

What should you take away from all this? Don’t be afraid to speak up when something in a contract isn’t clear; don’t “take their word for it”; and never put off creating what you love.

Categories: Making Sense of Contracts

Tags: Comics & Art, Contracts, copyright, Freelance

« The Ace Freelancer’s Guide to Asking Questions: Testing the Water Questions