How to Read a Contract

OK, folks, let’s talk about reading contracts.

This contract example was emailed to me the other day; no doubt you’ve seen it on other comics news sites.

I don’t know either of the parties and have no affiliation with either of them (though I did totally laugh at the review of the Twilight book CA did.)

I’m not interested in whether this is a fair contract or if either party behaved appropriately. Like I said, I don’t know them.

But I do know contracts and this one makes me cry.

It makes me cry because it is not clear.

It is not clear because someone other than the parties who signed it is reading it and trying to figure out exactly what the heck was intended.

Rule #1: A stranger should understand every contract you sign.

Why? Because if you ever have to use that contract, if you ever have to enforce it, a stranger is going to be the one reading it and determining what you can and cannot do.

So pass your next contract off to a friend or spouse and ask them to tell you what you’re agreeing to. If their understanding doesn’t match up with yours, fix the contract.

With that rule in mind, let’s march through this together, shall we?

Rule #2: Read a contract like you’re editing a story.

Whenever you read a contract, use your editor eyes. Editors concern themselves with language and what it communicates; that should be your concern.

And your goal? Clarity; see Rule #1.

Rule #3: Words mean things; explain what you mean when you use them.

In this particular contract we have a few choice examples of words that are not defined and so, to a stranger, might not make perfect sense.

My three votes for Hall of Shame: are “INKS,” “profits” and “an extra 10%.”

“INKS” is the least offensive of the three because there is a plausible argument that it means something.

In contracts, if a word is undefined but has a standard meaning within the industry to which the contract applies, that definition is used. The fancy lawyerly way of saying this is “industry standard.”

Seems like using an industry standard term would be very helpful shorthand, yes?

OK, when was the last time a group of artists all agreed what something meant?

“INKS” is just too vague; it looks like it could be an acronym or a bad INXS cover band. The term needs to be fleshed out at least a little bit. Me, I’d say, “the inked line work of the art constituting ‘10th Muse 800’ (collectively ‘the Work’)” instead. Also, I might want to mention how many pages that “Work” consisted of. 15? 500?

I would do that so that if there ever were a dispute about what the term meant, there wouldn’t have to be an argument over which “industry standard” definition to use; I’ve provided enough detail in the contract to avoid that argument.

Our next two Hall of Shamers share the same problem: they appear to mean something, but don’t.

Quick, what are “profits”?

“Oh, Katie, everyone knows that profits are what you have when you take the total amount of sales of a thing and subtract the total amount of costs necessary to make that thing.”

OK. Which costs? The costs for the paper and ink only? What about the editor’s salary? What about the postage? Rent on the building where the publisher’s office is? Taxes? Which taxes? What percentage of those taxes?

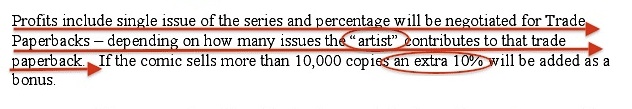

You’ll see the contract lamely attempts to define “profits.” Unfortunately, the sentence in which it attempts to do so is incomplete, is missing articles and has subjects and verbs in serious disagreement.

Also, the definition talks about the type of sales that will be included in figuring out “profits” but it doesn’t provide any information about how that calculation will be figured out.

Profits are about calculations because profits are math. The type of sales included in that calculation are the information that goes into the calculation, the integers.

For the definition of profits to be complete, we need to know what we’re supposed to do with those integers. That information is missing, and because it’s missing the word “profits” is nearly meaningless.

There is a similar problem with “an extra 10%.” An extra 10% of what? Of what you’ve made in “profits”? Well how can you make an extra 10% of an amount you can’t figure out?

Also, do you notice what that “extra 10%” is predicated on? “If the comic sells more than 10,000 copies….” What kind of copies? Single issue? Does it count if the copy is included in an anthology? What about those “Trade Paperbacks” the contract mentions? Do copies in those count toward the 10,000??

These two gems will help you remember Rule #4: If math is important, show your work in the contract.

Man, I bet you didn’t know someone could get that riled up about how a one page contract is written, did you? Well, guess what?

I’m not finished.

I’ve got a whole lot more to say about why this isn’t written well and how you can learn to be a better contract reader by reviewing it. But we’ve covered a lot of ground so far and now seems like a good time for a breather.

To recap the rules thus far:

Rule #1: A stranger should understand every contract you sign.

Rule #2: Read a contract like you’re editing a story.

Rule #3: Words mean things; explain what you mean when you use them.

Rule #4: If math is important, show your work in the contract.

I’d say that’s a darn good start to better understanding how to read a contract you’re being asked to sign. Come back tomorrow and we’ll dig even deeper into questions you should ask & eyebrows you should arch.

Categories: Making Sense of Contracts

Thank you very much.

It was very helpful!