Understanding Rates in Context

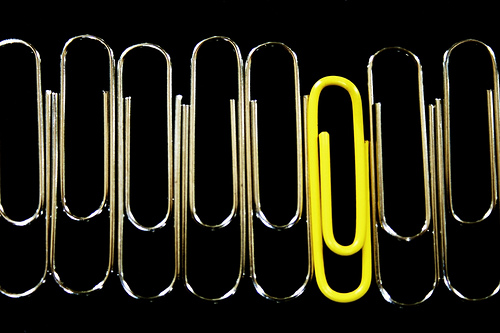

If I could wave my magic negotiation wand and change just one thing that would help artists and freelancers in their negotiations it would be this: I would have them share information with one another about what they’re paid.

Despite popular belief, power, bravado and money do not determine who the victor is in a negotiation. How well you do in a negotiation depends on how much information you have about what you’re negotiating over.

Having access to information is only the first step, though. Once you have the information, you have to understand it if you want to be able to use it to your advantage. This may sound obvious. But everyone, including me, has made this mistake in negotiations. (I made it in a negotiation to purchase literally millions of dollars in software and it nearly tanked the deal; I figured out my mistake and it worked out in the end, thankfully.)

FairPageRates.com came out with the results of their 2015 survey detailing what comic book creators were paid for their work by various publishers. The survey has a ton of great information in it and I thought it would make for a helpful real life example of how to make sure you understand information before you use it in a negotiation.

Not a comic book creator? Never fear. These same ideas will apply in your industry too, you may just have to ask the questions a little bit differently.

Is this apple really an orange?

When professionals share their rates and use shorthand to describe the work they did to get that rate, it’s easy to conflate types of work that are actually very different.

In the Fair Page Rates survey “Work For Hire” and “Page Rate” are listed together. Looking at the survey question, there isn’t a distinction between the page rate a creator has earned on work for hire jobs–where the creator retains no rights to the work–and rates where the creator owns the work. This is important because, typically, rates are lower when the creator retains the rights to the work. The creator will be able to make money from sales so the publisher doesn’t offer as much money up front.

Whenever you gather information about rates in your industry, do your best to determine if the rate is for the work you do, or work that’s similar to what you do. If it’s for work that’s similar, it’s still helpful, but how you use it in negotiations will be different than how you’d use information on rates for work that is exactly like what you’re being asked to do.

What are you buying with your signature?

When you sign an agreement with a publisher or someone licensing your work, you are buying their services. You are paying for those services with your intellectual property. Don’t buy blindly! Make sure you understand what you’re getting for your IP.

There are many different publishers listed in the survey, which is great because it gives a broad view of the industry (you want publishers to compete against one another for talent), but to really know if a $50 page rate at one publisher is the same as $50 at another publisher, you have to know what services come with that rate.

Here are the questions I’d want to ask if I was considering publishing my book with a particular company: How much marketing will they do? What’s the average cost for publishing a book at this publisher? What are the expenses that go into that cost? How often do their creator owned books pay out? What’s the average length of time before a book starts paying royalties? How often will I get paid? Are there ever problems with this publisher paying creators?

Even when you work a run of the mill gig with a client, you’re investing in that person or company. By working with them you can’t work with anyone else during at time. Make sure the job, and the client, are worth investing in.

What’s the math say?

I encourage anyone signing a contract to do the math to make sure they understand exactly what they’re being paid before they sign the agreement.

“But, Katie, it’s right there in the contract, duh. It says I’ll get 50% of the net profits. Easy peasy.”

OK, so you are entitled to 50% of what exactly?

“Net profits” means the amount of money that remains after expenses are deducted from sales (ymmv, all contracts define this term a bit differently). To do the math we’ll need to know the cost of making the book and the price the book will sell for. If we’ve asked questions (see above) we can make educated guesses, otherwise we’ll need to do some research before picking numbers.

I’m going to pick random numbers for our math here; don’t assume these numbers are tied to real life costs or sales.

Let’s say the book is going to sell for $12.95 and let’s assume the cost to make the book is $15K. Your book will have to sell 1159 copies before it breaks even. That’s nearly 1200 sales before you see any money.

Is that good? Without knowing the publisher’s average sales numbers for new books at that price point, it’s hard to say. Maybe? Maybe not.

If you don’t ask questions to figure out what you’re buying with your signature, you won’t be able to do the math to figure out what you’re likely to make from the project. And if you don’t know what you’re going to make from the project, why are you signing the contract?

I’m excited to see sites like FairPageRates.com and Who Pays Writers. I think they’re doing good and valuable work, and I hope more sites like these pop up so that freelancers can share information about rates with one another.

But I don’t want the conversation to stop there. I want us to keep sharing information so rates can be understood in context. Because when they’re understood in context, the information is invaluable.

Categories: The Rest